Sample Chapter

LIVE BY CHANCE, LOVE BY CHOICE, KILL BY PROFESSION

Chapter One: FNG

3 May 1970

Copyright © 2017 Roy Mark All rights reserved.

Sitting on a bar stool in Charlie Company’s Officers’ Club in Tay Ninh West, Warrant Officer (WO1) Sterling Cody and the other officers were relieving stress and tension, one beer at a time; Cody was several beers into the process.

The pilots and crews of Charlie Company were exhausted after three days of non‑stop flying into Cambodia. Ten to fourteen hours of solid flying made for very long and tiring days.

Cody had been in‑country for only two months, so he was still considered an FNG (Nam speak for f---ing new guy), and as such, his adrenaline had flowed double‑time as green tracers streaked past the windshield of his Huey. His aircraft commander (Pilot in Command) had looked so calm, with a “just another day at the office” manner and tone to his voice, and he didn’t seem to realize, or at least didn’t acknowledge, that their lives could end suddenly with any one of the green tracers that whizzed by. Now that Cody was safely back at base and inside the O‑Club, also known as the Officers’ Club, Cody was replacing his diminishing adrenaline with beer—lots of beer.

South Vietnamese forces had crossed over the Cambodian border on 30 April 1970, and with U.S. forces following soon afterward, the Cambodian Incursion was in full swing. The political objective of the campaign was to demonstrate the success of President Nixon’s Vietnamization program, to buy time so that U.S. forces could be safely withdrawn, and—according to a Nixon speech—to uphold U.S. ideals and credibility.

Political objectives meant little to the infantrymen—the grunts—and aircrews dodging bullets, mortars, and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). Their objective was to stay alive and to kill as many of the forty thousand enemy troops as possible that had amassed in the eastern border regions of Cambodia. Capturing or destroying munitions and supplies, although not as personally satisfying, was also part of their mission. They sent tons of rice stores back to South Vietnam. Rice that couldn’t be sent back across the border was destroyed.

When Sterling Cody finally made it back to Tay Ninh West on 3 May, he, like his aircraft commander and crew, was physically exhausted. Nevertheless, he had one more duty to perform before he could call it a day. After shutting down, Cody’s aircraft commander reminded him and his crew chief that the bird was due for an “MOC.” An MOC was merely a “maintenance operations check.” MOCs were performed periodically, and in this case, after 25 hours. MOCs were carried out by co‑pilots and crew chiefs. They were not such a big deal, unless you had been flying in harrowing conditions for twelve to fourteen hours.

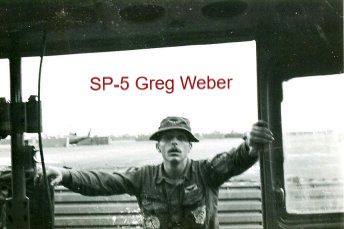

Cody instructed the crew chief, a young SP‑5 named Greg Weber, to get everything ready for the MOC, saying that he would return shortly. Weber had been in‑country a while and knew exactly where the FNG co‑pilot was headed.

The pilots and crews of Charlie Company were exhausted after three days of non‑stop flying into Cambodia. Ten to fourteen hours of solid flying made for very long and tiring days.

Cody had been in‑country for only two months, so he was still considered an FNG (Nam speak for f---ing new guy), and as such, his adrenaline had flowed double‑time as green tracers streaked past the windshield of his Huey. His aircraft commander (Pilot in Command) had looked so calm, with a “just another day at the office” manner and tone to his voice, and he didn’t seem to realize, or at least didn’t acknowledge, that their lives could end suddenly with any one of the green tracers that whizzed by. Now that Cody was safely back at base and inside the O‑Club, also known as the Officers’ Club, Cody was replacing his diminishing adrenaline with beer—lots of beer.

South Vietnamese forces had crossed over the Cambodian border on 30 April 1970, and with U.S. forces following soon afterward, the Cambodian Incursion was in full swing. The political objective of the campaign was to demonstrate the success of President Nixon’s Vietnamization program, to buy time so that U.S. forces could be safely withdrawn, and—according to a Nixon speech—to uphold U.S. ideals and credibility.

Political objectives meant little to the infantrymen—the grunts—and aircrews dodging bullets, mortars, and rocket-propelled grenades (RPGs). Their objective was to stay alive and to kill as many of the forty thousand enemy troops as possible that had amassed in the eastern border regions of Cambodia. Capturing or destroying munitions and supplies, although not as personally satisfying, was also part of their mission. They sent tons of rice stores back to South Vietnam. Rice that couldn’t be sent back across the border was destroyed.

When Sterling Cody finally made it back to Tay Ninh West on 3 May, he, like his aircraft commander and crew, was physically exhausted. Nevertheless, he had one more duty to perform before he could call it a day. After shutting down, Cody’s aircraft commander reminded him and his crew chief that the bird was due for an “MOC.” An MOC was merely a “maintenance operations check.” MOCs were performed periodically, and in this case, after 25 hours. MOCs were carried out by co‑pilots and crew chiefs. They were not such a big deal, unless you had been flying in harrowing conditions for twelve to fourteen hours.

Cody instructed the crew chief, a young SP‑5 named Greg Weber, to get everything ready for the MOC, saying that he would return shortly. Weber had been in‑country a while and knew exactly where the FNG co‑pilot was headed.

Being a pilot with the 229th Assault Aviation Battalion did come with the advantage of returning to base and cold beer, even if it was after dawn‑to‑dusk flying. Cody had come to the realization that flying combat missions was not only stressful but also physically exhausting. Cold beer always helped.

After his first cold beer at the O-Club, the tensions of the day began to subside. By his third or fourth beer, Sterling had lost track of time and didn’t realize that it was past 2100 hours; he was past due on the flight line for the MOC.

Oh well, he thought, I’ll head for the flight line after I finish this beer.

“OK sir, time for the MOC.”

Cody only managed to catch a glimpse of his crew chief in his peripheral vision as he was lifted onto Greg’s shoulders in the typical fireman’s carry. Draped over the shoulders of his crew chief, his left wrist in Greg’s firm grip, the other hand still holding his half‑finished beer, Sterling protested, albeit a mild protest that came with a chuckle.

“How in the hell can I drink my beer with my head at the 6 o’clock?”

“I’ll have you upright in a second, sir,” was Greg’s respectful but firm reply.

The other officers in the club glanced over, but they didn’t think the site of a WO1 being carried out of the club over the shoulders of an enlisted man was at all unusual, surely not worthy of interrupting the business at hand—the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol.

After his first cold beer at the O-Club, the tensions of the day began to subside. By his third or fourth beer, Sterling had lost track of time and didn’t realize that it was past 2100 hours; he was past due on the flight line for the MOC.

Oh well, he thought, I’ll head for the flight line after I finish this beer.

“OK sir, time for the MOC.”

Cody only managed to catch a glimpse of his crew chief in his peripheral vision as he was lifted onto Greg’s shoulders in the typical fireman’s carry. Draped over the shoulders of his crew chief, his left wrist in Greg’s firm grip, the other hand still holding his half‑finished beer, Sterling protested, albeit a mild protest that came with a chuckle.

“How in the hell can I drink my beer with my head at the 6 o’clock?”

“I’ll have you upright in a second, sir,” was Greg’s respectful but firm reply.

The other officers in the club glanced over, but they didn’t think the site of a WO1 being carried out of the club over the shoulders of an enlisted man was at all unusual, surely not worthy of interrupting the business at hand—the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol.

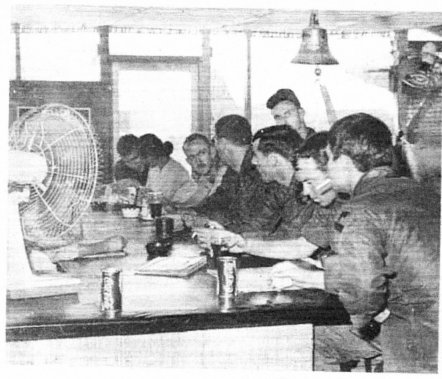

Inside the O-Club at Tay Ninh West

Notice the bell in the background. Should anyone walk into the club and forget to remove his hat, a mad dash to ring the bell would ensue, which would require the Soldier wearing the hat to buy a round of drinks for the entire bar.

Notice the bell in the background. Should anyone walk into the club and forget to remove his hat, a mad dash to ring the bell would ensue, which would require the Soldier wearing the hat to buy a round of drinks for the entire bar.

At the flight line, Greg unceremoniously dumped the co‑pilot into the right seat of their Huey.

On Greg’s, “Untied and clear,” Cody’s attention was focused on the task at hand. He went through the starting procedure and brought the aircraft up to 6600 RPM. Then, after Cody had ensured that all gauges were in the proper range, Greg Weber walked up next to the co‑pilot’s seat.

“OK sir— shut her down.”

With that, the MOC was completed. After securing their bird, co‑pilot and crew chief headed back to the bar.

Inside the O-Club, Cody offered Greg a beer. It was a simple gesture; it conveyed, without spoken words, Cody’s appreciation and that there were no hard feelings. Greg accepted the beer and headed off to his rack to stack a few Z’s. Zero dark early came fast, and they had missions to fly the next day.

WO1 Sterling Cody arrived in Vietnam in mid‑March 1970. He wanted to fly with and fight with the best, so he had volunteered for duty with the First Cavalry Division. The First Cav was, after all, known as “The First Team,” and nothing short of The First Team would do for Cody. The First Cav had many units fighting in South Vietnam, so the only unknown to the FNG was where First Cav would see fit to send him. His orders were cut soon enough, and he learned that he was headed for the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion.

When WO1 Sterling Cody reported to the commanding officer (CO) of the 229th in Tay Ninh West, he learned that the battalion was composed of three Huey Lift companies and one attack helicopter company. The Huey companies were Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie, and the attack helicopter company was Delta. The Hueys were primarily used for troop transport and were lightly armed with 7.62mm M60 machine guns mounted on each side. The Cobra attack helicopters of Delta Company were more heavily armed. They brought to the fight six M134 Miniguns that fired one thousand to four thousand rounds per minute of 7.62mm ammunition, 2.75-inch folding‑fin aerial rockets, 40mm grenade launchers, and newer models that had the 20mm M61 Vulcan Gatling‑style rotary cannon. The Cobra attack helicopter was a formidable offensive weapon. The attack helicopters were generally referred to as “gunships,” and the lightly armed Hueys were called “slicks.”

Over the course of a couple of quick orientation flights, Cody learned the lay of the land and Charlie Company’s procedures. Radio call signs of the battalion’s companies were committed to memory, along with radio frequencies. Charlie Company’s call sign was “North Flag,” which meant little to the nineteen‑year‑old FNG at the time, but he soon began to hear the older guys proudly refer to themselves as “North Flaggers.” There was an esprit de corps within Charlie Company that Sterling Cody admired. Now, he too was a North Flagger, and he would soon learn why the title was a badge of honor.

“Hitting the ground running” may have applied had he been a grunt, but with Cody, it was more a case of “hitting the sky flying.” The First Cav was pushing up into the Dog’s Head Area of III Corps, and contact with the enemy became more intense as they got close to the border. Once they were inside Cambodia, the enemy seemed to be everywhere. A lot could be said about the Viet Cong (VC)—“Charlie” for short—and the more professional North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers: they were brave, resourceful, numerous, and now, on the run.

The pilots and crews of Charlie Company would generally start the day flying combat assaults. They would rendezvous at a pre‑designated location (usually a fire support base) and then hook up with the infantry troops and their Cobra gunship escorts.

It was all new and exciting for Cody, but he was glad to be flying as peter‑pilot (co‑pilot) with experienced aircraft commanders, who were good—really good. There was a lot to take in and a lot to learn.

After completing the helicopter assaults, the flights would break up and proceed with individual resupply missions. Everything seemed routine to the old hands, but to Cody and the other FNGs, it was indoctrination by fire.

Even the FNGs could tell that Cambodia was different from South Vietnam. The enemy inside Cambodia was not the irregular VC but regular NVA forces. They were well organized and well entrenched—a formidable foe.

The North Vietnamese had been moving troops and equipment south into South Vietnam for years using the so-called “Ho Chi Minh Trail.” The trail’s origins traced back centuries to when it was nothing more than primitive footpaths used to facilitate trade in the region. In 1959, the North Vietnamese began improving the trail to supply arms to the VC in South Vietnam. By 1964, the supply capacity of the trail had become over 30 tons per day, and the trail facilitated the movement of a steady stream of NVA regulars into the South.

At the time that WO1 Cody first set eyes on the trail, it was no longer—if it ever was—the muddy trail that he had been led to believe it was. At Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne Pennsylvania, Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Course (ROTC) Cadet Cody had studied military tactics and watched films that depicted the Ho Chi Minh Trail as anything but the modern, sophisticated system of roads he was now seeing from his Huey. The “trail” was now an impressive network of paved roads complete with supply depots and fuel pipelines. The roads even had telephone poles along the sides and signs along the way, indicating the locations of motor pools, ammo dumps, and hospitals.

Cody, like most nineteen‑year‑olds, felt invincible, but after witnessing the sophistication and determination of his enemy, he began to question his youthful immortality. Even so, for as long as Cody could remember, he had always trusted his gut. He now took solace in his gut feeling that despite the carnage around him, he was going to be okay.

The Cav was now placing fire support bases right across the trail, and the pilots of Charlie Company were starting their days before dawn to prepare for the day’s missions. Each day that Cody flew into Cambodia, it seemed that there was yet another fire support base, each one a little deeper into Cambodia. The deeper the First Cav pushed into Cambodia, the more intense was the resistance they faced.

Missions usually called for a rendezvous at a predesignated location to hook up with First Cav grunts and Delta Company’s Cobra gunships. The rendezvous was generally at a fire support base, but it was sometimes at sites in the field.

The areas they were to launch assaults on were often softened up with fifteen minutes of artillery prep fire. Air strikes were sometimes called in—depending on the enemy situation—and they were controlled by an Air Force forward air controller (FAC) flying overhead. The FACs flew O-1 Bird Dog or OV-10 Broncos. The Bird Dog was a small two‑seat propeller aircraft, and the Broncos were turboprop light attack and observation aircrafts. They used 2.75-inch white phosphorus rockets to mark targets for the fighter aircraft.

And so it went on, mission after mission, day after day, as the North Flag Boys and the rest of First Cav systematically destroyed the previously untouchable enemy behind that imaginary line on the map known as the Cambodian border.

“What am I doing here?” was a thought that crossed the mind of every Soldier who found themselves in harm’s way, and the sky warriors were no exception. Cody experienced those feelings, too, but had conflicting emotions about them. He actually liked the Army, the adventure, the flying, and the adrenaline rush that seemed to last all day.

Soon, WO1 Sterling Cody noticed something odd. It didn’t happen often, but occasionally while flying in a combat zone, his mind would begin to drift. He would fly his Huey as if his feet on the rudders and his hands on the controls had a mind of their own. On these occasions, he would sometimes catch himself daydreaming of home. He often thought of his brother Jack, who was now back home after being wounded in Vietnam.

On Greg’s, “Untied and clear,” Cody’s attention was focused on the task at hand. He went through the starting procedure and brought the aircraft up to 6600 RPM. Then, after Cody had ensured that all gauges were in the proper range, Greg Weber walked up next to the co‑pilot’s seat.

“OK sir— shut her down.”

With that, the MOC was completed. After securing their bird, co‑pilot and crew chief headed back to the bar.

Inside the O-Club, Cody offered Greg a beer. It was a simple gesture; it conveyed, without spoken words, Cody’s appreciation and that there were no hard feelings. Greg accepted the beer and headed off to his rack to stack a few Z’s. Zero dark early came fast, and they had missions to fly the next day.

WO1 Sterling Cody arrived in Vietnam in mid‑March 1970. He wanted to fly with and fight with the best, so he had volunteered for duty with the First Cavalry Division. The First Cav was, after all, known as “The First Team,” and nothing short of The First Team would do for Cody. The First Cav had many units fighting in South Vietnam, so the only unknown to the FNG was where First Cav would see fit to send him. His orders were cut soon enough, and he learned that he was headed for the 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion.

When WO1 Sterling Cody reported to the commanding officer (CO) of the 229th in Tay Ninh West, he learned that the battalion was composed of three Huey Lift companies and one attack helicopter company. The Huey companies were Alpha, Bravo, and Charlie, and the attack helicopter company was Delta. The Hueys were primarily used for troop transport and were lightly armed with 7.62mm M60 machine guns mounted on each side. The Cobra attack helicopters of Delta Company were more heavily armed. They brought to the fight six M134 Miniguns that fired one thousand to four thousand rounds per minute of 7.62mm ammunition, 2.75-inch folding‑fin aerial rockets, 40mm grenade launchers, and newer models that had the 20mm M61 Vulcan Gatling‑style rotary cannon. The Cobra attack helicopter was a formidable offensive weapon. The attack helicopters were generally referred to as “gunships,” and the lightly armed Hueys were called “slicks.”

Over the course of a couple of quick orientation flights, Cody learned the lay of the land and Charlie Company’s procedures. Radio call signs of the battalion’s companies were committed to memory, along with radio frequencies. Charlie Company’s call sign was “North Flag,” which meant little to the nineteen‑year‑old FNG at the time, but he soon began to hear the older guys proudly refer to themselves as “North Flaggers.” There was an esprit de corps within Charlie Company that Sterling Cody admired. Now, he too was a North Flagger, and he would soon learn why the title was a badge of honor.

“Hitting the ground running” may have applied had he been a grunt, but with Cody, it was more a case of “hitting the sky flying.” The First Cav was pushing up into the Dog’s Head Area of III Corps, and contact with the enemy became more intense as they got close to the border. Once they were inside Cambodia, the enemy seemed to be everywhere. A lot could be said about the Viet Cong (VC)—“Charlie” for short—and the more professional North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers: they were brave, resourceful, numerous, and now, on the run.

The pilots and crews of Charlie Company would generally start the day flying combat assaults. They would rendezvous at a pre‑designated location (usually a fire support base) and then hook up with the infantry troops and their Cobra gunship escorts.

It was all new and exciting for Cody, but he was glad to be flying as peter‑pilot (co‑pilot) with experienced aircraft commanders, who were good—really good. There was a lot to take in and a lot to learn.

After completing the helicopter assaults, the flights would break up and proceed with individual resupply missions. Everything seemed routine to the old hands, but to Cody and the other FNGs, it was indoctrination by fire.

Even the FNGs could tell that Cambodia was different from South Vietnam. The enemy inside Cambodia was not the irregular VC but regular NVA forces. They were well organized and well entrenched—a formidable foe.

The North Vietnamese had been moving troops and equipment south into South Vietnam for years using the so-called “Ho Chi Minh Trail.” The trail’s origins traced back centuries to when it was nothing more than primitive footpaths used to facilitate trade in the region. In 1959, the North Vietnamese began improving the trail to supply arms to the VC in South Vietnam. By 1964, the supply capacity of the trail had become over 30 tons per day, and the trail facilitated the movement of a steady stream of NVA regulars into the South.

At the time that WO1 Cody first set eyes on the trail, it was no longer—if it ever was—the muddy trail that he had been led to believe it was. At Valley Forge Military Academy in Wayne Pennsylvania, Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Course (ROTC) Cadet Cody had studied military tactics and watched films that depicted the Ho Chi Minh Trail as anything but the modern, sophisticated system of roads he was now seeing from his Huey. The “trail” was now an impressive network of paved roads complete with supply depots and fuel pipelines. The roads even had telephone poles along the sides and signs along the way, indicating the locations of motor pools, ammo dumps, and hospitals.

Cody, like most nineteen‑year‑olds, felt invincible, but after witnessing the sophistication and determination of his enemy, he began to question his youthful immortality. Even so, for as long as Cody could remember, he had always trusted his gut. He now took solace in his gut feeling that despite the carnage around him, he was going to be okay.

The Cav was now placing fire support bases right across the trail, and the pilots of Charlie Company were starting their days before dawn to prepare for the day’s missions. Each day that Cody flew into Cambodia, it seemed that there was yet another fire support base, each one a little deeper into Cambodia. The deeper the First Cav pushed into Cambodia, the more intense was the resistance they faced.

Missions usually called for a rendezvous at a predesignated location to hook up with First Cav grunts and Delta Company’s Cobra gunships. The rendezvous was generally at a fire support base, but it was sometimes at sites in the field.

The areas they were to launch assaults on were often softened up with fifteen minutes of artillery prep fire. Air strikes were sometimes called in—depending on the enemy situation—and they were controlled by an Air Force forward air controller (FAC) flying overhead. The FACs flew O-1 Bird Dog or OV-10 Broncos. The Bird Dog was a small two‑seat propeller aircraft, and the Broncos were turboprop light attack and observation aircrafts. They used 2.75-inch white phosphorus rockets to mark targets for the fighter aircraft.

And so it went on, mission after mission, day after day, as the North Flag Boys and the rest of First Cav systematically destroyed the previously untouchable enemy behind that imaginary line on the map known as the Cambodian border.

“What am I doing here?” was a thought that crossed the mind of every Soldier who found themselves in harm’s way, and the sky warriors were no exception. Cody experienced those feelings, too, but had conflicting emotions about them. He actually liked the Army, the adventure, the flying, and the adrenaline rush that seemed to last all day.

Soon, WO1 Sterling Cody noticed something odd. It didn’t happen often, but occasionally while flying in a combat zone, his mind would begin to drift. He would fly his Huey as if his feet on the rudders and his hands on the controls had a mind of their own. On these occasions, he would sometimes catch himself daydreaming of home. He often thought of his brother Jack, who was now back home after being wounded in Vietnam.

I hope you enjoyed this sample chapter of

LIVE BY CHANCE, LOVE BY CHOICE, KILL BY PROFESSION

LIVE BY CHANCE, LOVE BY CHOICE, KILL BY PROFESSION

|

LIVE BY CHANCE, LOVE BY CHOICE, KILL BY PROFESSION is available in Paperback on Amazon.Com for $16.99. Amazon offers Free Shipping to their Prime Subscribers.

|

|

LIVE BY CHANCE, LOVE BY CHOICE, KILL BY PROFESSION, is available in Kindle eBook format for $6.99

|

|

A Special HARDBOUND EDITION of LIVE BY CHANCE, LOVE BY CHOICE, KILL BY PROFESSION

is now available exclusively on this website.

The cost for the hardbound copy is $23.00 plus $5.00 for delivery.

This edition is only available for delivery to U.S. Customers.

is now available exclusively on this website.

The cost for the hardbound copy is $23.00 plus $5.00 for delivery.

This edition is only available for delivery to U.S. Customers.