Neil "Beeper" Blume

The Anonymous Battle

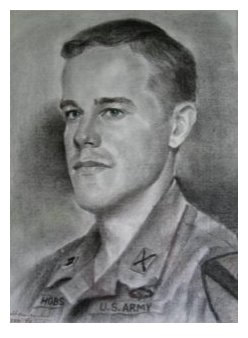

Capt. George K. Hobson - 1970 Pencil Drawing by a Vietnamese Street Artist.

Capt. George K. Hobson - 1970 Pencil Drawing by a Vietnamese Street Artist.

Dog’s Face, War Zone C, Republic of Vietnam, 26 March 1970:

A battle between the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Americans of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry (C-2/8) had been raging for most of the morning. By mid-day, the situation was becoming dire for the Americans. They were sustaining heavy casualties, and their ammunition was almost expended.

The seven-hundred battled-hardened NVA soldiers were commanded by Colonel Nguyen Tuong Lai. Charlie Company was commanded by Captain George K. Hobson.

By 1300 hours (1:00 p.m.) Charlie Company’s casualty rate was sixty-two percent. Of Hobson’s original force of seventy-nine men, forty-nine had been killed or severely wounded. With only thirty Sky Troopers fit to fight, Charlie Company was outnumbered nine to one. All attempts at medivac and resupply for the beleaguered Americans by air were repulsed by heavy ground fire, and additional pleas for resupply were as yet unanswered.

With the prospect of his entire company being wiped out fast becoming a probability, Captain Hobson radioed 2nd Battalion commander, Lieutenant Commander (LTC) Michael Conrad with a profound message:

A battle between the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Americans of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry (C-2/8) had been raging for most of the morning. By mid-day, the situation was becoming dire for the Americans. They were sustaining heavy casualties, and their ammunition was almost expended.

The seven-hundred battled-hardened NVA soldiers were commanded by Colonel Nguyen Tuong Lai. Charlie Company was commanded by Captain George K. Hobson.

By 1300 hours (1:00 p.m.) Charlie Company’s casualty rate was sixty-two percent. Of Hobson’s original force of seventy-nine men, forty-nine had been killed or severely wounded. With only thirty Sky Troopers fit to fight, Charlie Company was outnumbered nine to one. All attempts at medivac and resupply for the beleaguered Americans by air were repulsed by heavy ground fire, and additional pleas for resupply were as yet unanswered.

With the prospect of his entire company being wiped out fast becoming a probability, Captain Hobson radioed 2nd Battalion commander, Lieutenant Commander (LTC) Michael Conrad with a profound message:

"If you don't get ammunition here by 1530 (3:30 P.M.), don't bother. Just send body bags."

The hours passed; enemy fire intensified. The American's ability to resist diminished as their ammo dwindled. It appeared that every Soldier of Charlie Company would be killed or captured and that an entire U.S. Army company would be wiped out.

The Mission

Brigadier General (BG) George William Casey, Sr. (9 March 1922 – 7 July 1970) was Assistant Division Commander for Maneuver of 1st Cavalry Division. Casey was a hands-on guy that cared deeply for the welfare of his Soldiers. Casey was often on the ground with the companies of the Division, and to Hobson, his first words were always, “George, what do you need?” He had earned their deepest respect, and his Soldiers were willing, and often eager to follow him into battle.

From the sounds of the “body bags” radio call, an entire U.S. Army company was at risk of total annihilation and that was not going to happen on Casey’s watch.

It was a hectic day with action on several fronts but C-2/8’s situation, necessitated immediate action. Casey, a forty-eight-year-old one-star general, a qualified Huey pilot, took the co-pilot’s seat aboard a UH-1H Huey and spoke to the Aircraft Commander (Pilot‑in‑Command) like a high school football coach exhorting his quarterback in for the winning touchdown. But this was no game, —lives were at stake. The pilot readily agreed to fly the dangerous re-supply mission.

After loading the Huey with ammo, The warrant officer pilot and his brigadier general co-pilot blasted off on the re-supply mission. The fate of an entire U.S. Army company hung in the balance.

In the back of the Huey, BG Casey’s aide‑de‑camp sat among the ammo boxes and the Huey’s crew-chief and door‑gunner prepped their M‑60 machine guns. With no Cobra gunship support, the Huey’s two M-60s would be their only defense from what everyone on board knew would be a barrage of enemy fire.

It was just before 1530 hours (3:30 p.m.) as Casey’s Huey approached C-2/8’s location.

The pilot keyed his radio, “Inbound your location, pop smoke.”

A purple smoke grenade was thrown to mark the American’s location

“Roger, smoke out,” came the reply from the ground.

The pilot scanned the area and acknowledged, “I see goofy-grape.”

The radio operator on the ground replied, “Roger, confirm goofy grape. Come on in.”

The Huey pilot adjusted his heading toward the purple smoke and began setting up his approach.

The NVA, either after seeing the Americans’ purple smoke, or possibly knowing of the purple smoke by monitoring the American’s frequency popped a purple smoke grenade in an attempt at luring the Huey in for an easy kill.

On the ground, incoming fire from the NVA began to lessen ever so slightly, but only because the bad-guys were starting to direct their fire at the incoming Huey. In Charlie Company’s 2nd Platoon—The “Scotch” Platoon—Radio Operator (RTO) Ken Woodward (a.k.a. Mississippi) saw the NVA’s goofy-grape smoke and knew he had to act, —FAST!

Woodward grabbed his radio's handset and called the company command post. There could be no doubt of the urgency of his message as he shouted that the enemy had just popped the same color smoke.

Fearing that the Huey pilot might be misdirected to the enemy’s position, Hobson directed the Huey to abort the approach to any smoke. He told the pilot that he’d talk him into the company’s perimeter. Captain Hobson, unable to see the Huey through the thick trees, talked the Huey in based on the intensity of the “wop-wop-wop” sound of the Huey’s main rotor. Slowly, the sound intensified until the Huey’s crew thought that they were directly over Charlie Company’s position.

In the air, small arms fire became intense, and the “ping” sounds of AK-47 bullets hitting the Huey meant that they were close to the surrounded C-2/8.

The jungle canopy was thick, and there was no opening for the Huey to sit down, and with no more than meters separating the good guys from the bad, it would have to be a precision “Hover-Down and Kick-Out” operation.

When the Huey was close enough overhead for Woodward and Hobson to see the hovering Huey, they were horrified to see the number of green tracer rounds hitting the Huey. And, knowing that four regular bullets normally separated each tracer, they were amazed at the courage of the pilots in maintaining a steady hover to drop ammo to the beleaguered troops.

RTO Woodward later said:

“NVA Bullets Impacting the Huey Sounded Like a Kansas Hailstorm on a Tin Roof.”

NVA bullets were putting holes in the Huey, but amazingly none hit critical components. The general’s aide-de-camp and one of the Huey's crew, however, weren't as lucky. They were wounded over the drop‑zone.

Probably believing that he was over the good-guy’s position, and with his ship’s skids in—not above, but in—the tree-tops, the pilot directed his crew to begin kicking ammo out the open doors. On the ground, the troopers saw the ammo landing just outside of their eastern perimeter.

Two Americans, supported by covering fire, immediately ran toward enemy fire to retrieve the ammo, —heroes all.

From the sounds of the “body bags” radio call, an entire U.S. Army company was at risk of total annihilation and that was not going to happen on Casey’s watch.

It was a hectic day with action on several fronts but C-2/8’s situation, necessitated immediate action. Casey, a forty-eight-year-old one-star general, a qualified Huey pilot, took the co-pilot’s seat aboard a UH-1H Huey and spoke to the Aircraft Commander (Pilot‑in‑Command) like a high school football coach exhorting his quarterback in for the winning touchdown. But this was no game, —lives were at stake. The pilot readily agreed to fly the dangerous re-supply mission.

After loading the Huey with ammo, The warrant officer pilot and his brigadier general co-pilot blasted off on the re-supply mission. The fate of an entire U.S. Army company hung in the balance.

In the back of the Huey, BG Casey’s aide‑de‑camp sat among the ammo boxes and the Huey’s crew-chief and door‑gunner prepped their M‑60 machine guns. With no Cobra gunship support, the Huey’s two M-60s would be their only defense from what everyone on board knew would be a barrage of enemy fire.

It was just before 1530 hours (3:30 p.m.) as Casey’s Huey approached C-2/8’s location.

The pilot keyed his radio, “Inbound your location, pop smoke.”

A purple smoke grenade was thrown to mark the American’s location

“Roger, smoke out,” came the reply from the ground.

The pilot scanned the area and acknowledged, “I see goofy-grape.”

The radio operator on the ground replied, “Roger, confirm goofy grape. Come on in.”

The Huey pilot adjusted his heading toward the purple smoke and began setting up his approach.

The NVA, either after seeing the Americans’ purple smoke, or possibly knowing of the purple smoke by monitoring the American’s frequency popped a purple smoke grenade in an attempt at luring the Huey in for an easy kill.

On the ground, incoming fire from the NVA began to lessen ever so slightly, but only because the bad-guys were starting to direct their fire at the incoming Huey. In Charlie Company’s 2nd Platoon—The “Scotch” Platoon—Radio Operator (RTO) Ken Woodward (a.k.a. Mississippi) saw the NVA’s goofy-grape smoke and knew he had to act, —FAST!

Woodward grabbed his radio's handset and called the company command post. There could be no doubt of the urgency of his message as he shouted that the enemy had just popped the same color smoke.

Fearing that the Huey pilot might be misdirected to the enemy’s position, Hobson directed the Huey to abort the approach to any smoke. He told the pilot that he’d talk him into the company’s perimeter. Captain Hobson, unable to see the Huey through the thick trees, talked the Huey in based on the intensity of the “wop-wop-wop” sound of the Huey’s main rotor. Slowly, the sound intensified until the Huey’s crew thought that they were directly over Charlie Company’s position.

In the air, small arms fire became intense, and the “ping” sounds of AK-47 bullets hitting the Huey meant that they were close to the surrounded C-2/8.

The jungle canopy was thick, and there was no opening for the Huey to sit down, and with no more than meters separating the good guys from the bad, it would have to be a precision “Hover-Down and Kick-Out” operation.

When the Huey was close enough overhead for Woodward and Hobson to see the hovering Huey, they were horrified to see the number of green tracer rounds hitting the Huey. And, knowing that four regular bullets normally separated each tracer, they were amazed at the courage of the pilots in maintaining a steady hover to drop ammo to the beleaguered troops.

RTO Woodward later said:

“NVA Bullets Impacting the Huey Sounded Like a Kansas Hailstorm on a Tin Roof.”

NVA bullets were putting holes in the Huey, but amazingly none hit critical components. The general’s aide-de-camp and one of the Huey's crew, however, weren't as lucky. They were wounded over the drop‑zone.

Probably believing that he was over the good-guy’s position, and with his ship’s skids in—not above, but in—the tree-tops, the pilot directed his crew to begin kicking ammo out the open doors. On the ground, the troopers saw the ammo landing just outside of their eastern perimeter.

Two Americans, supported by covering fire, immediately ran toward enemy fire to retrieve the ammo, —heroes all.

Aftermath

It was a miracle that the Huey made it through the hail of NVA small arms fire. AK-47 bullets had peppered the ship and wounded two onboard, including BG Casey’s aide-de-camp. The pilot was the ultimate authority and could have aborted the mission at any point, and no one would have blamed him. His courage and steely determination to deliver his life-saving cargo of ammo changed the course of the battle. Then, with great airmanship, the Huey pilot flew his heavily damaged ship the four kilometers to Fire Support Base (FSB) Illingworth.

After an emergency landing at Illingworth, the Huey was immediately inspected for damage. A quick count revealed sixteen hits. The ship was declared to be unserviceable and was airlifted out slung below a CH-47 Chinook helicopter.

Captain Hobson commented later that based on his observation during the hover-down and kick-out that he saw many more tracers hitting the Huey than the initial count of sixteen. Regardless of the count, the pilot’s steely nerves in holding his ship steady as the supplies were kicked out undeniably saved Charlie Company.

Captain Hobson’s men of Charlie Company lived to fight on that day and the days to come, and they felt that they owed their lives to that pilot. They marveled at the courage of that pilot, and they never forgot. He was a hero in their eyes, but in the fog of war, no one got his name.

The pilot shrugged and went on with his business; just another day at the office for the hero that would remain unnamed for forty-five years.

A few days after The Anonymous Battle, BG Casey went home on scheduled leave. Before returning to Vietnam Brigadier General George William Casey, Sr. was promoted to Major General (MG) in a ceremony at the Pentagon. Upon returning to Vietnam, the new two-star general took over command of the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division.

Four months after the Anonymous Battle, MG Casey flew from his headquarters at Phouc Vinh to the Army hospital at Cam Ranh to visit wounded troops. Casey was co-pilot of the UH-1H which carried the Aircraft Commander and five passengers. In bad weather, the Huey crashed into a mountain near Bao Loc, South Vietnam. All onboard died in the crash.

MG Casey was survived by his wife, three daughters and two sons.

Major General George William Casey, Sr. was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on 23 July 1970.

After an emergency landing at Illingworth, the Huey was immediately inspected for damage. A quick count revealed sixteen hits. The ship was declared to be unserviceable and was airlifted out slung below a CH-47 Chinook helicopter.

Captain Hobson commented later that based on his observation during the hover-down and kick-out that he saw many more tracers hitting the Huey than the initial count of sixteen. Regardless of the count, the pilot’s steely nerves in holding his ship steady as the supplies were kicked out undeniably saved Charlie Company.

Captain Hobson’s men of Charlie Company lived to fight on that day and the days to come, and they felt that they owed their lives to that pilot. They marveled at the courage of that pilot, and they never forgot. He was a hero in their eyes, but in the fog of war, no one got his name.

The pilot shrugged and went on with his business; just another day at the office for the hero that would remain unnamed for forty-five years.

A few days after The Anonymous Battle, BG Casey went home on scheduled leave. Before returning to Vietnam Brigadier General George William Casey, Sr. was promoted to Major General (MG) in a ceremony at the Pentagon. Upon returning to Vietnam, the new two-star general took over command of the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division.

Four months after the Anonymous Battle, MG Casey flew from his headquarters at Phouc Vinh to the Army hospital at Cam Ranh to visit wounded troops. Casey was co-pilot of the UH-1H which carried the Aircraft Commander and five passengers. In bad weather, the Huey crashed into a mountain near Bao Loc, South Vietnam. All onboard died in the crash.

MG Casey was survived by his wife, three daughters and two sons.

Major General George William Casey, Sr. was buried in Arlington National Cemetery on 23 July 1970.

U.S. Government Photo

U.S. Government Photo

George William Casey, Sr.

Major General, United States Army

9 March 1922 – 7 July 1970

General Casey had served in the Korean War and was in command of the 1st Cavalry Division at the time of his death.

The Charlie Family

LTC George K. Hobson (U.S. Army Retired), former commanding officer of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Division organized THE CHARLIE FAMILY in 2010. His goal was to provide brothers in arms, forged in the crucible of war the fellowship that time and distance could not destroy.

Their first reunion was held in Watertown, South Dakota in September 2010. The association has honored a select few outsiders membership based on their shared Vietnam War experiences. Two artillery officers that were on FSB Illingworth with Charlie Company have been welcomed into The Charlie Family. Captain Hobson’s Forward Observer in Cambodia and two Cobra gunship pilots that flew with C-2/8 during firefights are also part of the family. Daniel E. Tyler, a Huey pilot who took KIA’s (Killed in Action) off FSB Illingworth on 1 April 1970 and flew Captain Hobson on his last combat assault as commanding officer of C-2/8 is also now part of The Charlie Family. Some family members of C-2/8’s fallen heroes (Gold Star Family members) were also welcomed into the family. The Charlie Family now includes seventy-nine members.

Since their first reunion, The Charlie Company Family have gathered for reunions every other year. The College of the Ozarks near Branson, Missouri has been a focal point of each gathering. The college has adopted The Charlie Family, and its president Doctor Jerry C. Davis welcomes members at each reunion. Invariably, the subject of The Anonymous Battle would come up during the reunions, and unfailingly, C-2/8 vets wondered aloud who the Huey pilot was that saved their asses on 26 March 1970. George Hobson vowed to do his damnedest to find out.

Their first reunion was held in Watertown, South Dakota in September 2010. The association has honored a select few outsiders membership based on their shared Vietnam War experiences. Two artillery officers that were on FSB Illingworth with Charlie Company have been welcomed into The Charlie Family. Captain Hobson’s Forward Observer in Cambodia and two Cobra gunship pilots that flew with C-2/8 during firefights are also part of the family. Daniel E. Tyler, a Huey pilot who took KIA’s (Killed in Action) off FSB Illingworth on 1 April 1970 and flew Captain Hobson on his last combat assault as commanding officer of C-2/8 is also now part of The Charlie Family. Some family members of C-2/8’s fallen heroes (Gold Star Family members) were also welcomed into the family. The Charlie Family now includes seventy-nine members.

Since their first reunion, The Charlie Company Family have gathered for reunions every other year. The College of the Ozarks near Branson, Missouri has been a focal point of each gathering. The college has adopted The Charlie Family, and its president Doctor Jerry C. Davis welcomes members at each reunion. Invariably, the subject of The Anonymous Battle would come up during the reunions, and unfailingly, C-2/8 vets wondered aloud who the Huey pilot was that saved their asses on 26 March 1970. George Hobson vowed to do his damnedest to find out.

The Search

WO1 Neil "Beeper" Blume —Republic of Vietnam, 1970

WO1 Neil "Beeper" Blume —Republic of Vietnam, 1970

In 2005 Captain Hobson—now Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) George K. Hobson, U.S. Army (Retired)—began searching the internet for information about, among other things related to his time in Vietnam, The Anonymous Battle. Learning the identity of the Huey pilot that saved his infantry company from annihilation was always a goal, but one in which he had little hopes of achieving.

In his internet search, Hobson ran across an article written in 1995 by Daniel E. Tyler (Former U.S. Army Officer). Tyler, a Second Lieutenant and Huey Pilot in 1970, had written about evacuating the Killed in Action from the scene of the Battle of FSB Illingworth on 1 April 1970. Hobson contacted Tyler, and the two warriors exchanged notes of their time in Vietnam. George Hobson came to rely on Dan Tyler as a source of information about helicopter operations in the 1st Cav.

In 2015, ten years after their initial contact, Dan Tyler was at a Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association (VHPA) Reunion in Washington, D.C. On the last evening of the reunion, Dan and other pilots from Charlie Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion (C/229th AHB) were gathered reminiscing, and as old Soldiers often do, telling war stories.

One of Dan’s C/229th AHB comrades that evening was Neil Blume. Neil’s radio call-sign in Vietnam was “Beeper” and Beeper had become a nickname that has stuck with Neil ever since, at least with his pilot friends.

With six or eight old helicopter pilots sitting around drinking beer and telling war stories, it took a while for each to tell a story or two. Toward the end of the session, Neil “Beeper” Blume began telling a story about a resupply mission that he flew with a “senior” officer. As Beeper told more of the details of that mission, Dan Tyler began to sit up straight in his chair, and his attention became laser-focused on Beeper’s words. Tyler wasn’t sure, but the mission sounded a lot like the re-supply mission flown by the unknown pilot and BG Casey.

After the 2015 VHPA reunion, Dan Tyler told George Hobson what he had learned and Hobson, in turn, contacted Neil Blume. Hobson and Blume compared memories of the events of 26 March 1970, and the two determined that Neil “Beeper” Blume was the pilot that The Charlie Family had been searching for those many years.

In his internet search, Hobson ran across an article written in 1995 by Daniel E. Tyler (Former U.S. Army Officer). Tyler, a Second Lieutenant and Huey Pilot in 1970, had written about evacuating the Killed in Action from the scene of the Battle of FSB Illingworth on 1 April 1970. Hobson contacted Tyler, and the two warriors exchanged notes of their time in Vietnam. George Hobson came to rely on Dan Tyler as a source of information about helicopter operations in the 1st Cav.

In 2015, ten years after their initial contact, Dan Tyler was at a Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association (VHPA) Reunion in Washington, D.C. On the last evening of the reunion, Dan and other pilots from Charlie Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion (C/229th AHB) were gathered reminiscing, and as old Soldiers often do, telling war stories.

One of Dan’s C/229th AHB comrades that evening was Neil Blume. Neil’s radio call-sign in Vietnam was “Beeper” and Beeper had become a nickname that has stuck with Neil ever since, at least with his pilot friends.

With six or eight old helicopter pilots sitting around drinking beer and telling war stories, it took a while for each to tell a story or two. Toward the end of the session, Neil “Beeper” Blume began telling a story about a resupply mission that he flew with a “senior” officer. As Beeper told more of the details of that mission, Dan Tyler began to sit up straight in his chair, and his attention became laser-focused on Beeper’s words. Tyler wasn’t sure, but the mission sounded a lot like the re-supply mission flown by the unknown pilot and BG Casey.

After the 2015 VHPA reunion, Dan Tyler told George Hobson what he had learned and Hobson, in turn, contacted Neil Blume. Hobson and Blume compared memories of the events of 26 March 1970, and the two determined that Neil “Beeper” Blume was the pilot that The Charlie Family had been searching for those many years.

Recognition

Thirty-one members of The Charlie Family gathered for their biennial reunion in Branson, Missouri on 6 September 2018. The five-day reunion was held at the Missouri State Vietnam Veterans Memorial, College of the Ozarks, Missouri and was filled with events honoring a few extraordinary people.

The reunion began with a Missouri Bar-B-Que on Thursday followed by a luncheon on Friday the 7th in which awards were presented.

Among those honored by The Charlie Family was Neil “Beeper” Blume. To a man, veterans of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Division felt that Neil Blume was their hero. Had Warrant Officer Blume not agreed to fly the re-supply mission, or if he had turned back in the face of massive enemy fire, the entire company would have been killed or captured by a brutal enemy.

The reunion began with a Missouri Bar-B-Que on Thursday followed by a luncheon on Friday the 7th in which awards were presented.

Among those honored by The Charlie Family was Neil “Beeper” Blume. To a man, veterans of Charlie Company, 2nd Battalion, 8th Cavalry Division felt that Neil Blume was their hero. Had Warrant Officer Blume not agreed to fly the re-supply mission, or if he had turned back in the face of massive enemy fire, the entire company would have been killed or captured by a brutal enemy.

George K. Hobson, Charlie Company’s commanding officer during The Anonymous Battle, had invited Neil to the reunion and The Family, in a gesture of gratitude and generosity, paid all expenses for Neil and his wife, Patricia. Neil and Pat drove from their home near Herman, Minnesota to Branson along with their three sons and their wives.

Blume was presented with a framed letter of appreciation from George Hobson on behalf of The Charlie Family. The coin insert at the bottom represents the Missouri State Vietnam Veterans Memorial at the College of the Ozarks.

Blume was presented with a framed letter of appreciation from George Hobson on behalf of The Charlie Family. The coin insert at the bottom represents the Missouri State Vietnam Veterans Memorial at the College of the Ozarks.

Blume was also presented with a framed letter of accommodation from the commanding officer of the 1st Cavalry Division, Major General Paul T. Calvert. The 1st Cav coin insert at the bottom acknowledges Blume's excellence in his performance of duty.

General Calvert's letter is difficult to read in this photo, so I created a reproduction that you can read by clicking on the link.

|

Carol Stacy, wife of C-2/8 medic David Dedrick made a special hand-made quilt that was presented to Neil Blume on behalf of the men and women of The Charlie Family. The centerpiece of the quilt is the 1st Cavalry Division's emblem below a black patch which reads:

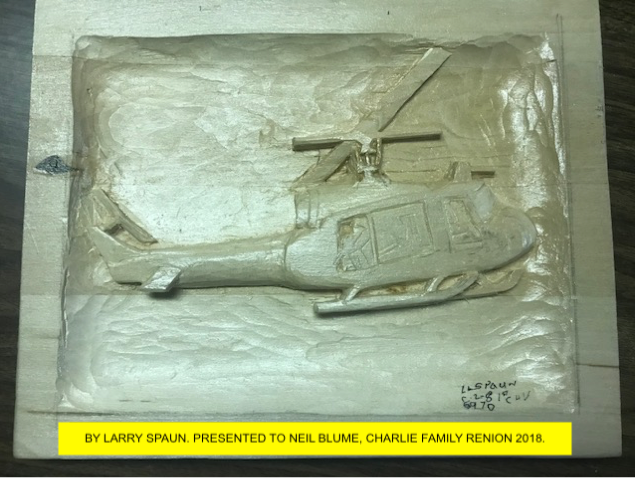

CW2 Neil Blume A true warrior and hero! 26 March 1970 Holding the quilt for the photo are Neil and and his wife Pat. Blume was also presented with a woodcarving of a Huey helicopter which was hand-carved by C-2/8 vet Larry Spaun. |

|

The Charlie Family gathered at the Missouri State Vietnam Veterans Memorial where they offered prayers and placed a wreath. They then went to The Walk of Honor where pavers had recently been emplaced to honor CW2 Neil Blume and others. In the photo, Neil and Pat Blume along with their three sons and daughters-in-law stand in the Missouri State Vietnam Veterans Memorial near where the paver honors Neil's heroic re‑supply mission of 26 March 1970. |

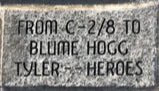

The paver that the C-2/8 veterans of The Anonymous Battle placed in The Walk of Honor is indicative of their feelings for Huey Pilot Neil "Beeper" Blume.

The Charlie Family installed a paver in the Walk of Honor to memorialize pilots Neil Blume, Joseph C. Hogg, and Daniel E. Tyler. Blume and Tyler flew for Charley Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion and Hogg flew for 2nd Battalion, 20 Artillery (Aerial Rocket Artillery).

The slide show below shows some photos relevant to The Anonymous Battle of 1970 and The Charlie Family Reunion of 2018.

L to R: Spec4 Adam Jipson, General (4-Star) George Casey, Jr., and Spec4 Kevin Blume. General Casey was commander of all troops in Iraq.

L to R: Spec4 Adam Jipson, General (4-Star) George Casey, Jr., and Spec4 Kevin Blume. General Casey was commander of all troops in Iraq.

Thirty-five years after WO1 Neil Blume and Brigadier General George Casey flew their dangerous re-supply mission, Neil’s son, Kevin, posed for a photo in Iraq with George Casey’s son, General George Casey, Jr. Both Soldiers were unaware of their father’s mutual connection to The Anonymous Battle.

George W. Casey, Jr. retired in 2011 with the rank of General (4‑Stars) after serving as the 36th Chief of Staff of the United States Army.

On the ground, company commanders developed a personal sense about each soldier in their command. Their Soldiers became more than a name; more than a face. They became the commander’s responsibility, not only professionally, but on a personal level. To the commander, the responsibility of life and death was entrusted. Few commanding officers could take this responsibility lightly.

Pilots were removed from that intimacy with individuals on the ground. Entire units were known only by impersonal call signs. Voices over the radio had no face, and no personality other than the occasional inflection of stress as a battle raged. That remoteness was emphasized as pilots flew multiple missions to different units on a given day. Even so, the pilots recognized those voices on the radio as American Soldiers—brothers in arms.

The Vietnam-era helicopter pilots' ethos of personal dedication and commitment shrugged aside the anonymity. Their actions reflected the true spirit of American citizen-warriors.

Pilots were removed from that intimacy with individuals on the ground. Entire units were known only by impersonal call signs. Voices over the radio had no face, and no personality other than the occasional inflection of stress as a battle raged. That remoteness was emphasized as pilots flew multiple missions to different units on a given day. Even so, the pilots recognized those voices on the radio as American Soldiers—brothers in arms.

The Vietnam-era helicopter pilots' ethos of personal dedication and commitment shrugged aside the anonymity. Their actions reflected the true spirit of American citizen-warriors.

Neil Blume is an icon of those aerial warriors

Creation of this webpage honoring CW2 Neil "Beeper" Blume and the men of C/2-8 would not have been possible without the input of LTC George K. Hobson (U.S. Army, Retired), C/2-8 Veteran Ken Woodward, and Charlie Company, 229th Assault Helicopter Battalion pilot Daniel E. Tyler. Their assistance on this project is greatly appreciated as is their service to

The United States of America.

The United States of America.