An Adobe Acrobat version of

The Lost Battalion and The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast

is available by clicking on the link below:

The Lost Battalion and The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast

is available by clicking on the link below:

| Click here to upload file | |

| File Size: | 717 kb |

| File Type: | |

The Lost Battalion

and

The Galloping Ghost of the Java Coast

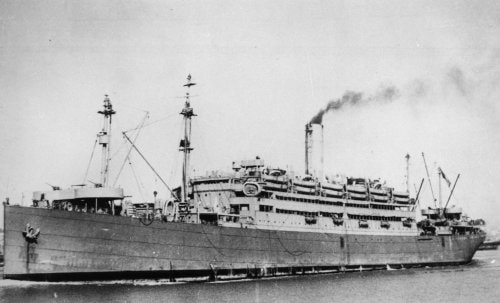

The USS Republic (AP-33) arriving in Brisbane, Australia harbor, December 1941

The USS Republic (AP-33) arriving in Brisbane, Australia harbor, December 1941

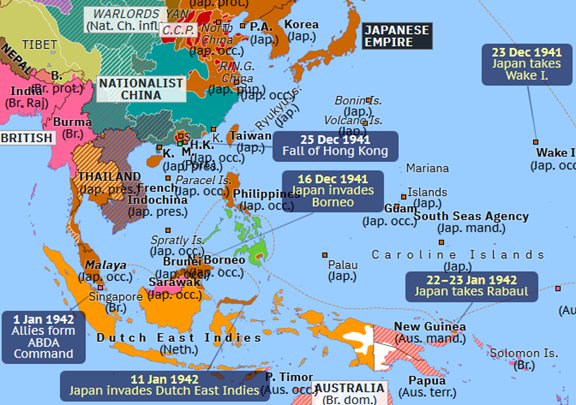

In November 1940, the 2nd Battalion, 131st Field Artillery Regiment, 36th Division of the Texas National Guard, was activated. After training for one year, the battalion shipped out to the West Coast, and on 22 November 1941, with the United States observing an uneasy peace, the battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Blutcher S. Tharp of Amarillo, Texas boarded the troop transport USS Republic (AP‑33) in San Francisco. The soldiers knew their destination only by the code name, “Plum.”

The 28,000‑ton USS Republic was built in 1907 in Belfast, Ireland, for a German Steamship Company. The U.S. confiscated the ship during World War‑I and commissioned her USS President Grant (SP‑3014) in 1917. In 1920 the President Grant was transferred to the U.S. Army and renamed USAT Republic, then in July of 1941, the Republic was transferred to the Navy and commissioned USS Republic (AP–33). Her armament consisted of one 5 inch and four 3-inch mounts.

The 2nd Battalion, 131st Field Artillery onboard the USS Republic, reached Pearl Harbor on 29 November 1941. In Pearl, the Republic joined with three other transport and cargo ships and the cruiser USS Pensacola (CA‑24) to form a convoy for the remainder of the trip to Plum. The convoy sailed west on 30 November, leaving behind a peaceful Pearl Harbor. Once at sea, destination Plum was revealed to be Manila Bay in the Philippine Islands.

On 7 December, the peace was shattered at Pearl Harbor by the surprise Japanese attack. That same day, the USS Republic, en route to the Philippines had recently crossed the equator, and the men of the 2nd Battalion along with the Sailors of the Republic were beginning the traditional ritual of initiating those men crossing the equator for the first time, into the “Mysterious Realm of Neptune Rex.” Officers and enlisted men alike were initiated. During the ceremony, usually quite joyous, the botswain's call (a loud whistle) blasted to get everyone's attention.

The Republic’s captain began, “Now hear this, all hands, a message from the President of the United States: This is to let you know that a state of war now exist between the United States and Japan. Govern your actions accordingly. Good luck!”

The word that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor quickly spread throughout the ship. The ships of the convoy increased their spacing and began wartime zigzagging.

In mid‑December the convoy carrying the Texans arrived in the Fiji Islands for fuel and supplies. After replenishment, the convoy sailed for the Philippines. En route, the news was received that the Japanese had invaded the Philippines; the convoy was ordered to sail instead to Brisbane, Australia. The Texans of the 2nd Battalion arrived in Brisbane on 23 December 1941. The battalion spent Christmas in Brisbane, but before 1941 ended, it was aboard another ship, this time the Dutch icebreaker SS Bloemfontein.

The 2nd Battalion, aboard the Bloemfontein, made a brief stop at Port Darwin before sailing for the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) island of Java and arrived in the Javanese port of Surabaya on 11 January 1942. The reality of war became all too real to the Texans when they saw the harbor strewn with partially sunk ships and the docks heavily damaged by Japanese bombs. The 538 Texans disembarked in Surabaya, Java, and were placed under the direct command of the Dutch government. It was an unceremonious welcome to World War II.

From Surabaya, the Texans moved inland to a Dutch military post (Camp Singasari) near the town of Malang. Meanwhile, the Japanese were landing troops on the island of Borneo located just North of Java and later in January on the nearby island of Celebes (now Sulawesi). By early February, both islands were securely in Japan’s possession. During February of 1942, the Japanese also invaded and captured Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies islands of Sumatra and Bali. The Japanese were then poised to take the main island of Java, the Texans’ new home.

The Republic’s captain began, “Now hear this, all hands, a message from the President of the United States: This is to let you know that a state of war now exist between the United States and Japan. Govern your actions accordingly. Good luck!”

The word that the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor quickly spread throughout the ship. The ships of the convoy increased their spacing and began wartime zigzagging.

In mid‑December the convoy carrying the Texans arrived in the Fiji Islands for fuel and supplies. After replenishment, the convoy sailed for the Philippines. En route, the news was received that the Japanese had invaded the Philippines; the convoy was ordered to sail instead to Brisbane, Australia. The Texans of the 2nd Battalion arrived in Brisbane on 23 December 1941. The battalion spent Christmas in Brisbane, but before 1941 ended, it was aboard another ship, this time the Dutch icebreaker SS Bloemfontein.

The 2nd Battalion, aboard the Bloemfontein, made a brief stop at Port Darwin before sailing for the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) island of Java and arrived in the Javanese port of Surabaya on 11 January 1942. The reality of war became all too real to the Texans when they saw the harbor strewn with partially sunk ships and the docks heavily damaged by Japanese bombs. The 538 Texans disembarked in Surabaya, Java, and were placed under the direct command of the Dutch government. It was an unceremonious welcome to World War II.

From Surabaya, the Texans moved inland to a Dutch military post (Camp Singasari) near the town of Malang. Meanwhile, the Japanese were landing troops on the island of Borneo located just North of Java and later in January on the nearby island of Celebes (now Sulawesi). By early February, both islands were securely in Japan’s possession. During February of 1942, the Japanese also invaded and captured Malaya, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies islands of Sumatra and Bali. The Japanese were then poised to take the main island of Java, the Texans’ new home.

In February, the British decided not to defend the island of Java, and with Holland occupied by the Nazis, the 538 Texans and a few free‑Dutch soldiers became the sole Allied defense of Java. The Allies, however, were not going down without a fight.

On 18 February 1942, a Japanese invasion fleet left Cam Ranh Bay in occupied French Indo‑China escorted by the 5th Destroyer Squadron.

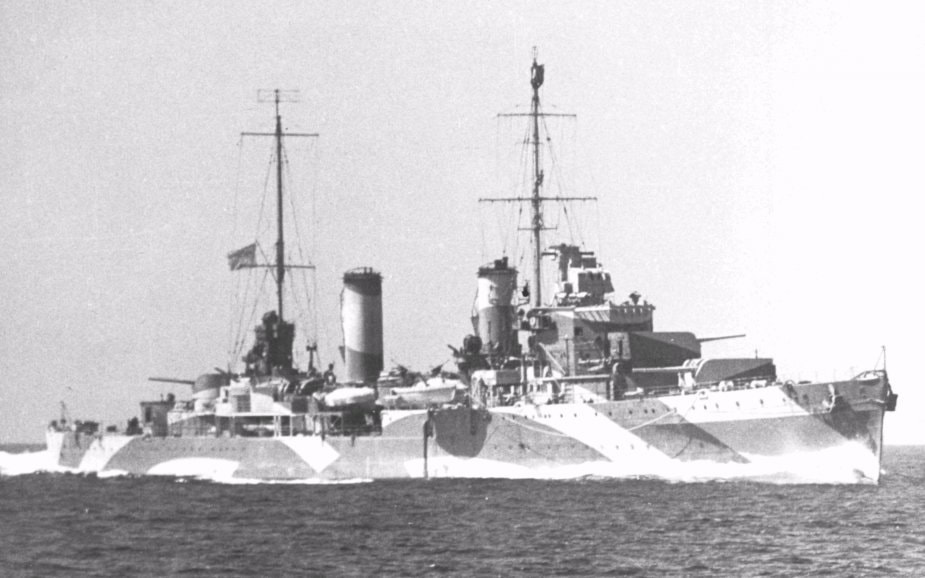

Meanwhile, an Allied force consisting of the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) and the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth had been conducting operations north of Java in the Java Sea. Both ships had distinguished themselves in minor sea battles but were ordered to retreat to Australia.

On 18 February 1942, a Japanese invasion fleet left Cam Ranh Bay in occupied French Indo‑China escorted by the 5th Destroyer Squadron.

Meanwhile, an Allied force consisting of the heavy cruiser USS Houston (CA-30) and the Australian light cruiser HMAS Perth had been conducting operations north of Java in the Java Sea. Both ships had distinguished themselves in minor sea battles but were ordered to retreat to Australia.

The Perth and Houston, under the command of Captain Albert Rooks, were proceeding west in the Java Sea, and as they entered the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, they spotted a line of Japanese transport ships near the Java Coast. They sunk four transport ships, including one carrying the Commanding General. Just then, the Japanese covering force consisting of three cruisers and nine destroyers arrived. The two Allied cruisers, despite being low on fuel and ammunition, attacked the Imperial warships.

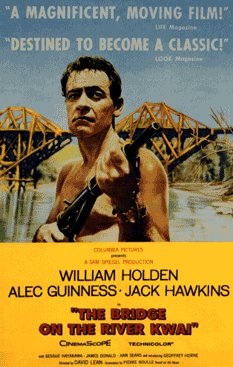

Hollywood's Movie Poster for

THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI

Hollywood's Movie Poster for

THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI

During a multi‑hour battle, the Japanese covering force fired eighty‑five torpedoes at the Allied ships before Houston and Perth sank to the muddy bottom of the Java Sea.

USS Houston’s complement of 1,011 men fought bravely throughout the engagement, but 625 were killed in the fighting or went down with the ship. After the order to abandon ship, 386 crewmen swam to the nearby shoreline, leaving their former home below the shallow waters off the Java Coast. The Japanese soon captured the oil‑soaked Sailors and Marines.

The world did not know Houston's fate for almost nine months, and the full story of her courageous fight was not entirely told until after the survivors were liberated from prison camps in 1945. Captain Rooks was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary heroism, and The USS Houston was unofficially given the title, “THE GALLOPING GHOST OF THE JAVA COAST.”

Nine days after the sinking of the Houston and the Perth, a message arrived at the 2nd Battalion from the Governor General’s office in Batavia (present‑day Jakarta).

The Texans stood in stunned silence as the message was read. “We are forced to surrender. It is useless to try to hold out any longer. You are ordered to surrender immediately with your men and equipment, unconditionally, to the Imperial Japanese Army. You are to wait with your men and equipment at Goerett [a nearby town].”

The Texans became Prisoners of War. The Japanese became conquerors. The Javanese became joyous after their liberation from 123‑years of Dutch Colonial rule. Their joy, however, soon dissipated when it became clear that their new masters were far crueler than their former colonizers.

As was the fate of the USS Houston, so too, the fate of the 2nd Battalion, was not known to the War Department for many months after their capture.

The family and friends of the Texans of the 2nd Battalion, began referring to their loved ones collectively as, “THE LOST BATTALION.”

The Texans soon met the Sailors and Marines of the USS Houston in POW camps in Tanjung Priok and later Batavia and a bond developed between the two that would last for the rest of their lives.

From Java, the POWs were shipped north to Singapore and were placed into Changi Prison. After several months in Changi, the POWs were transported by rail in cattle cars to Thailand to work on the enemy’s Burma‑Siam Railway Project

The rail project would eventually stretch 258 miles between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma.

Conditions along the entire 258 miles of the project were harsh and punitive. The fanatical Japanese soldiers treated the POWs and civilian slave laborers worse than beast of burden. The Javanese laborers that had cheered the arrival of the Japanese “liberators” to their island, only to be shipped north to work on the railway project, now found themselves working and dying alongside Dutch POWs.

An estimated 16,000 Allied POWs and 90,000 Asian laborers died of disease, sickness, and starvation at the hands of the Japanese Army. The number of POWs forced to work on the railway included 30,000 British; 18,000 Dutch; 13,000 Australian; and 700 Americans. The death toll included 6,540 British; 2,830 Dutch; 2,710 Australian; 220 Malay; 33 Indian; 5 New Zealand; and 356 Americans.

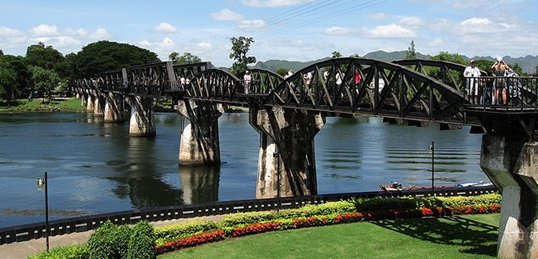

In 1957 Hollywood produced the film THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI, which was loosely based on the POW’s story of working on the Death Railroad, and particularly the construction of a railway bridge over the River Kwai. Filmed in Ceylon (present‑day Sri Lanka), the movie bridge was built in eight months by 500 workers and 35 elephants. The real bridge was built in just six months. Hollywood’s bamboo bridge was 50 feet above the water and 425 feet long.

THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI was the number one box‑office success of 1957. It won critical acclaim and seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

USS Houston’s complement of 1,011 men fought bravely throughout the engagement, but 625 were killed in the fighting or went down with the ship. After the order to abandon ship, 386 crewmen swam to the nearby shoreline, leaving their former home below the shallow waters off the Java Coast. The Japanese soon captured the oil‑soaked Sailors and Marines.

The world did not know Houston's fate for almost nine months, and the full story of her courageous fight was not entirely told until after the survivors were liberated from prison camps in 1945. Captain Rooks was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his extraordinary heroism, and The USS Houston was unofficially given the title, “THE GALLOPING GHOST OF THE JAVA COAST.”

Nine days after the sinking of the Houston and the Perth, a message arrived at the 2nd Battalion from the Governor General’s office in Batavia (present‑day Jakarta).

The Texans stood in stunned silence as the message was read. “We are forced to surrender. It is useless to try to hold out any longer. You are ordered to surrender immediately with your men and equipment, unconditionally, to the Imperial Japanese Army. You are to wait with your men and equipment at Goerett [a nearby town].”

The Texans became Prisoners of War. The Japanese became conquerors. The Javanese became joyous after their liberation from 123‑years of Dutch Colonial rule. Their joy, however, soon dissipated when it became clear that their new masters were far crueler than their former colonizers.

As was the fate of the USS Houston, so too, the fate of the 2nd Battalion, was not known to the War Department for many months after their capture.

The family and friends of the Texans of the 2nd Battalion, began referring to their loved ones collectively as, “THE LOST BATTALION.”

The Texans soon met the Sailors and Marines of the USS Houston in POW camps in Tanjung Priok and later Batavia and a bond developed between the two that would last for the rest of their lives.

From Java, the POWs were shipped north to Singapore and were placed into Changi Prison. After several months in Changi, the POWs were transported by rail in cattle cars to Thailand to work on the enemy’s Burma‑Siam Railway Project

The rail project would eventually stretch 258 miles between Ban Pong, Thailand, and Thanbyuzayat, Burma.

Conditions along the entire 258 miles of the project were harsh and punitive. The fanatical Japanese soldiers treated the POWs and civilian slave laborers worse than beast of burden. The Javanese laborers that had cheered the arrival of the Japanese “liberators” to their island, only to be shipped north to work on the railway project, now found themselves working and dying alongside Dutch POWs.

An estimated 16,000 Allied POWs and 90,000 Asian laborers died of disease, sickness, and starvation at the hands of the Japanese Army. The number of POWs forced to work on the railway included 30,000 British; 18,000 Dutch; 13,000 Australian; and 700 Americans. The death toll included 6,540 British; 2,830 Dutch; 2,710 Australian; 220 Malay; 33 Indian; 5 New Zealand; and 356 Americans.

In 1957 Hollywood produced the film THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI, which was loosely based on the POW’s story of working on the Death Railroad, and particularly the construction of a railway bridge over the River Kwai. Filmed in Ceylon (present‑day Sri Lanka), the movie bridge was built in eight months by 500 workers and 35 elephants. The real bridge was built in just six months. Hollywood’s bamboo bridge was 50 feet above the water and 425 feet long.

THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI was the number one box‑office success of 1957. It won critical acclaim and seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

The real bridge at Kanchanaburi, Thailand, has become a significant tourist attraction.

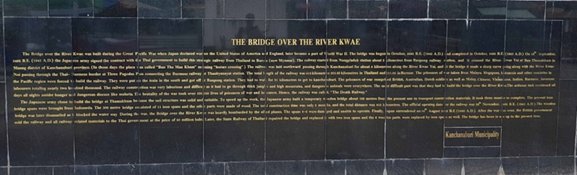

The local Kanchanaburi Municipality erected a monument near the bridge. The black wall with gold‑colored print is a brief history of the “Great Pacific War” and the construction of the railway from Thailand to Burma.

Copied below are the 554 words inscribed on the Kanchanaburi Monument:

The Bridge over the River Kwae was built during the Great Pacific War when Japan declared war on the United States of America and England, later became a part of World War II. The bridge was begun in October 2485 B.E. (1942 A.D) and completed in October, 2486 B.E. (1943 A.D.) On 16th September, 2485 B.E. (1942 A.D.) the Japanese army signed the contract with the Thai government to build this strategic railway from Thailand to Burma (Now Myanmar). The railway started from Nongpladuk station about 5 kilometers from Banpong railway station, and it crossed the River Kwae at Ban Thamakham in Muang district of Kanchanaburi province. (In those days the place was called “Ban Tha Maa Kham” meaning “horses crossing.”) The railway was laid northward passing through Kanchanaburi for about 4 kilometers along the River Kwae Yai, and at the bridge it made a sharp curve going along with the River Kwae Noi passing through the Thai‑Burmese border at Three Padogas Pass connecting the Burmese railway at Thanbyuzayat station. The total length of the railway was 415 kilometers: 303.95 kilometers in Thailand and 111.05 kilometers in Burma. The prisoners of war taken from Malaya, Singapore, Indonesia and other countries in the Pacific region were forced to build the railway. They were put on the train in the south and got off at Bangpong station. They had to walk for 51 kilometers to get to kanchanburi. The prisoners of war comprised British, Australian, Dutch soldiers as well as Malay, Chinese, Vietnamese, Indian, Burmese, Javanese labourers totaling nearly two hundred thousand. The railway construction was very laborious and difficult as it had to go through thick jungles and high mountains, and dangerous animals were everywhere. The most difficult part was that they had to build the bridge over the River Kwae. The arduous task continued all days and nights amidst hunger and dangerous disease like malaria. The brutality of the war took over 100,000 lives of prisoners of war and laborers. Hence, the railway was, “The Death Railway.”

The Japanese army chose to build the bridge at Thamakham because the soil structure was solid and suitable. To speed up the work, the Japanese army built a temporary wooden bridge about 100 meters from the present one to transport construction materials. It took three months to complete. The present iron bridge spans were brought from Indonesia. The 300 meter bridge consist of 11 iron spans and the other parts were made of wood. The total construction time was only 6 months, and the total distance was 415 kilometers. The official opening date for the railway was 28th November, 2486 B.E. (1943 A.D). The wooden bridge was later dismantled as it blocked the water way during the war, the Bridge over the River Kwae was heavily bombarded by the allied planes. The spans 4 – 6 were damaged and unable to operate. Finally, Japan surrendered on 15th August 2488 B.E (1945 A.D.). After the war was over, the British government sold the railway and all railway related materials to the Thai government at the price of 50 million baht. Later, the State Railway of Thailand repaired the bridge and replaced it with two iron spans and the 6 wooden parts were replaced by iron spans as well. The bridge has been in use up to the present time.

Kanchanaburi Municipality

The Japanese army chose to build the bridge at Thamakham because the soil structure was solid and suitable. To speed up the work, the Japanese army built a temporary wooden bridge about 100 meters from the present one to transport construction materials. It took three months to complete. The present iron bridge spans were brought from Indonesia. The 300 meter bridge consist of 11 iron spans and the other parts were made of wood. The total construction time was only 6 months, and the total distance was 415 kilometers. The official opening date for the railway was 28th November, 2486 B.E. (1943 A.D). The wooden bridge was later dismantled as it blocked the water way during the war, the Bridge over the River Kwae was heavily bombarded by the allied planes. The spans 4 – 6 were damaged and unable to operate. Finally, Japan surrendered on 15th August 2488 B.E (1945 A.D.). After the war was over, the British government sold the railway and all railway related materials to the Thai government at the price of 50 million baht. Later, the State Railway of Thailand repaired the bridge and replaced it with two iron spans and the 6 wooden parts were replaced by iron spans as well. The bridge has been in use up to the present time.

Kanchanaburi Municipality

There are several factual errors contained in the inscription as well as numerous grammatical and punctuation errors. The most factual glaring mistake is that the inscription makes no mention of American POWs working or dying during the construction of the Railroad.

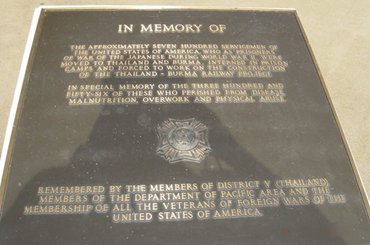

The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) of America erected a memorial at the bridge site and dedicated it to the Americans who worked on the railway and to those who died.

The Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) of America erected a memorial at the bridge site and dedicated it to the Americans who worked on the railway and to those who died.

The Plaque reads:

IN MEMORY OF

The approximately seven hundred servicemen of

The United States Of America, who as prisoners

of war of the Japanese during World War II, were

moved to Thailand and Burma, interned in prison

camps and forced to work on the construction

of the Thailand‑Burma Railway Project.

In special memory of the three hundred and

Fifty‑six of these who perished from disease,

malnutrition, overwork and physical abuse.

Remembered by the members of District V (Thailand),

members of the Department of Pacific Area and the

membership of all the Veterans of Foreign Wars of The

United States of America

The United States Of America, who as prisoners

of war of the Japanese during World War II, were

moved to Thailand and Burma, interned in prison

camps and forced to work on the construction

of the Thailand‑Burma Railway Project.

In special memory of the three hundred and

Fifty‑six of these who perished from disease,

malnutrition, overwork and physical abuse.

Remembered by the members of District V (Thailand),

members of the Department of Pacific Area and the

membership of all the Veterans of Foreign Wars of The

United States of America

According to the book LOST BATTALION by Kyle Thompson, 166 of the 2nd Battalion Texans and USS Houston Sailors and Marines died while working as slave labor on the Thailand to Burma Railroad. Of the 356‑total number of American deaths, Lost Battalion and USS Houston amounted to 47% of total deaths at the hands of their brutal captors.

For every mile of track laid, 412 Allied POWs and Asian laborers died from disease, malnutrition, physical abuse, or outright murder. The Allies aptly named the project:

For every mile of track laid, 412 Allied POWs and Asian laborers died from disease, malnutrition, physical abuse, or outright murder. The Allies aptly named the project:

“The Death Railroad”

Bibliography

Thompson, Kyle. LOST BATTALION: Railway of Death. New York, New York: ibooks,1994. Original title: A THOUSAND CUPS OF RICE

http://www.roy-mark.com/bridge.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/bridge_2.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/moh.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/lostbattalion/index.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/lost.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/bridge.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/bridge_2.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/moh.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.texasmilitaryforcesmuseum.org/lostbattalion/index.htm 5 March 2020

http://www.roy-mark.com/lost.htm 5 March 2020